Solving the 'Broken Calculator' problem the hard way

I don’t normally do LeetCode problems…

Although I really enjoy coding, and frequently make good use of those skills as part of my 9-5 job, I’ve never really spent much time solving challenges on LeetCode or similar sites. I enjoy the thought exercises, but haven’t “needed” the experience to get an edge in software interviews (although whether or not this should actually give anyone an edge is highly debatable), and when I do have time to sit down and write some code it’s usually to solve an immediate, practical problem. None of this is to say that I don’t or wouldn’t enjoy being able to do this, it’s just a fact of life for me.

So I almost ignored an opportunity last weekend when my brother pointed me toward an interesting entry and challenged me to submit a solution.

Note: you will likely have to sign up for an account with LeetCode to see the problem on their website. If you don’t feel like doing that, just keep reading - I’ll summarize it below.

…but when I do…

The puzzle was, as seems to often be the case, one that looked easy at first, until you go to write code to solve it. There are several variations on this problem, but here’s the version in this particular challenge:

You have a calculator that is somehow broken so badly that all that’s left functional is the screen (which can display numbers between 1 and 1 billion), and two other buttons. Oddly, these buttons are two that don’t show up on any calculator I’ve seen, namely a double and a decrement (by one) operation.

The challenge is to get from a starting number on the calculator to a given second number using only those two functions.

The example given is:

- Input: $x = 2, y = 3$

- Output: $2$

- Explanation: Use double operation, and then decrement operation $[ 2 \rightarrow 4 \rightarrow 3]$

Anyway, calculator vagaries aside, the code needed to solve this puzzle should:

- Given any starting number $x$

- Using only the double $(x = x \cdot 2)$ and/or decrement $(x = x - 1)$ operations

- Determine the minimum operations needed to arrive at arbitrarily chosen $y$

The immediately obvious, and (as far as I can tell) wrong way to look at this problem is to do what’s stated, and try to get from $x$ to $y$. Having done a few coding challenges before, I’ve learned that it’s often helpful to start by working backwards from the solution, and that turned out to be useful in this case as well.

Once I got to this backwards mindset, the rest fell into place pretty quickly:

- If $y$ is less than $x$:

- Decrement $x$ until it equals $y$ and return the number of operations. There is no doubling in this case.

- A quicker way to look this is to just return $x - y$

- If $y$ equals $x$, then return $0$

- If $y$ is greater than $x$:

- If $y$ is an odd number, increment $y$ by $1$ (since we’re going backwards, incrementing here is equivalent to decrementing if starting from $x$)

- If $y$ is an even number:

- If $y$ is greater than $x$, divide $y$ by $2$ (equivalent to doubling $x$, one of the two permitted operations).

- If $y$ is less than $x$, then increment $y$ until you arrive at $x$

- Loop through this sequence until $y$ is equal to $x$

This ends up looking like some variation of the below Python code:

# first pass algorithm

def min_ops(x: int, y: int) -> int:

if y < x:

return x - y

ops = 0

while y != x:

if y > x and y % 2 == 0:

y /= 2

else:

y += 1

ops += 1

return ops

# testing code

if __name__ == '__main__':

test_cases = [(2, 3, 2)]

for case in test_cases:

x, y, expected = case

result = min_ops(x, y)

if result != expected:

print(f"{x}->{y} should have been {expected}, but got {result}")

else:

print(f"Correctly solved {x}->{y} in {result} operations")

…I prefer a more complicated answer…

There’s absolutely nothing wrong with this algorithm. It gives the correct answer, it meets LeetCode’s criteria for memory usage and runtime, and it’s pretty easy to understand.

However… it really bugged me that I had to iterate through each state of the answer to arrive at the result. For really, really big numbers, this would take a long time. I know, I know… it doesn’t really matter, the answer is correct, it meets spec, “perfect is the enemy of good enough”, “premature optimization is the root of all evil”, and all that. In real life, I almost certainly would’ve stopped here unless there was a business reason for optimizing further. But it was the weekend, and although the weather was perfect for spending outside, and I had a ton of other side projects I wanted to get to, it couldn’t take too much longer to arrive at a solution I actually liked, right? … right??

Many hours and 18 sheets of scratch paper later…

Patterns are fun (if you’re a nerd)

Here we go.

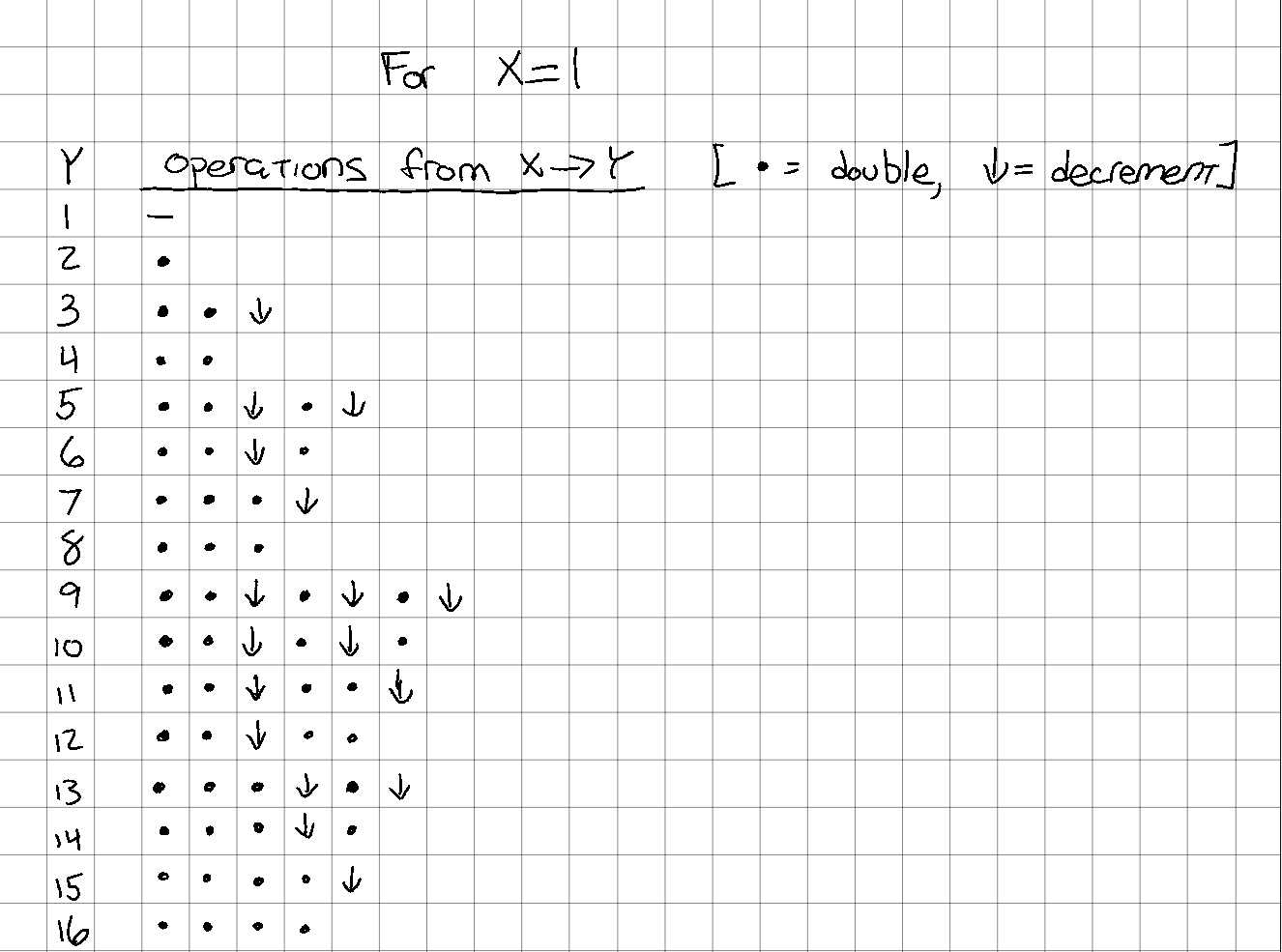

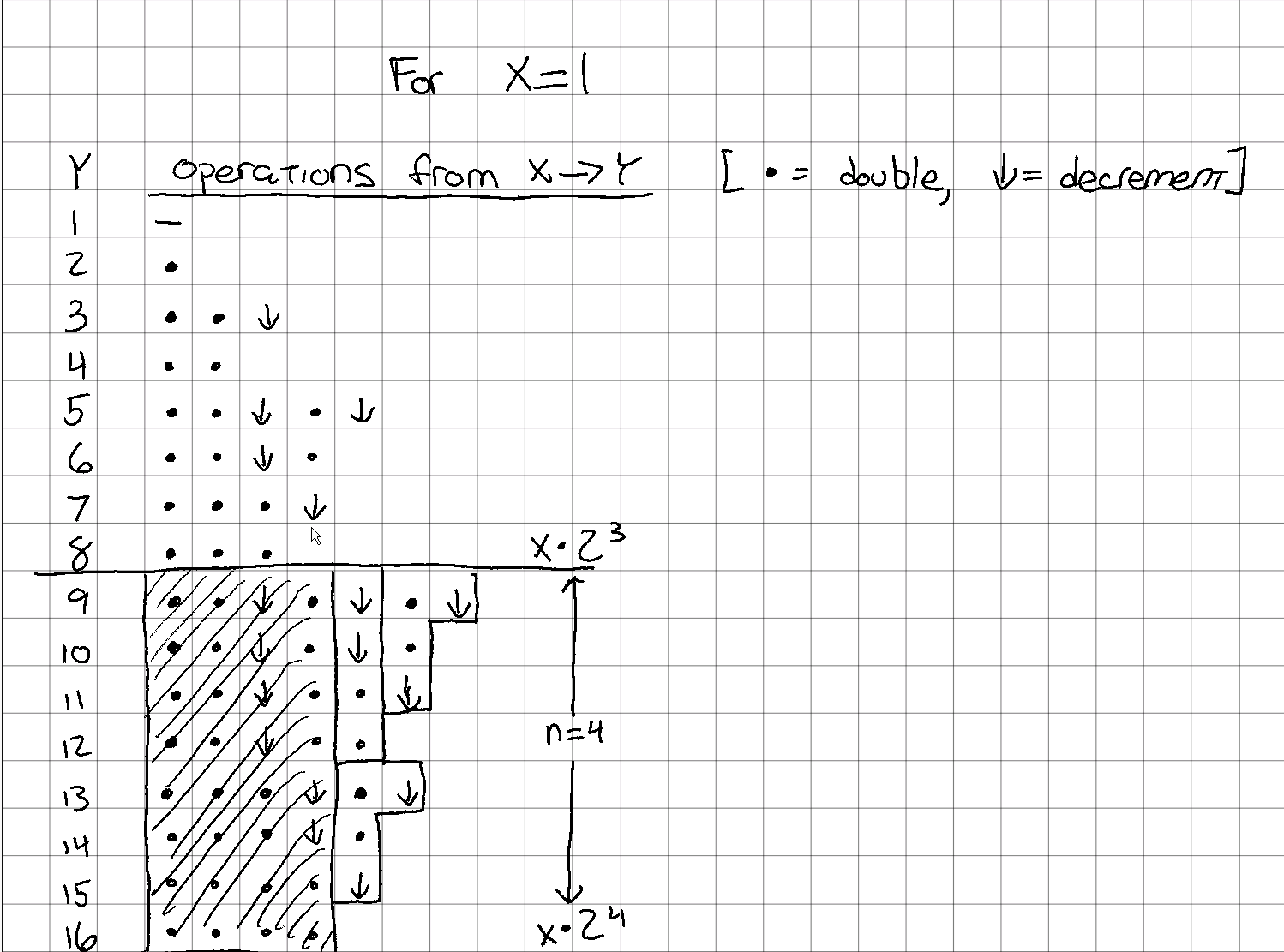

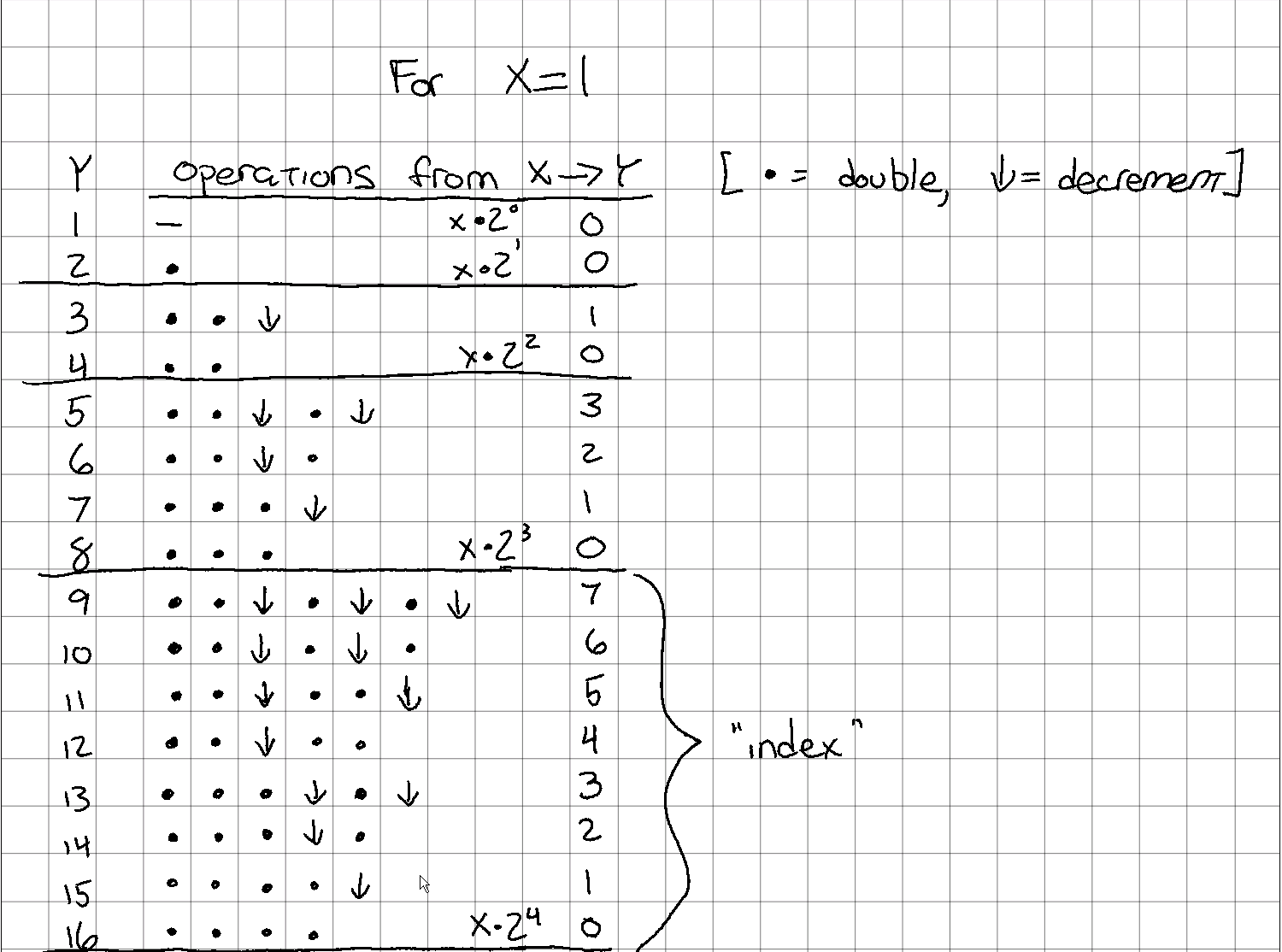

Let’s start with the case where $x$ is 1, and see what it takes to get to various $y$ values:

X=1 for various Y

A few things are definitely going on here:

- There is an even/odd component, since the last operation for any odd number must be a decrement, and the last operation for any even number may not be a decrement.

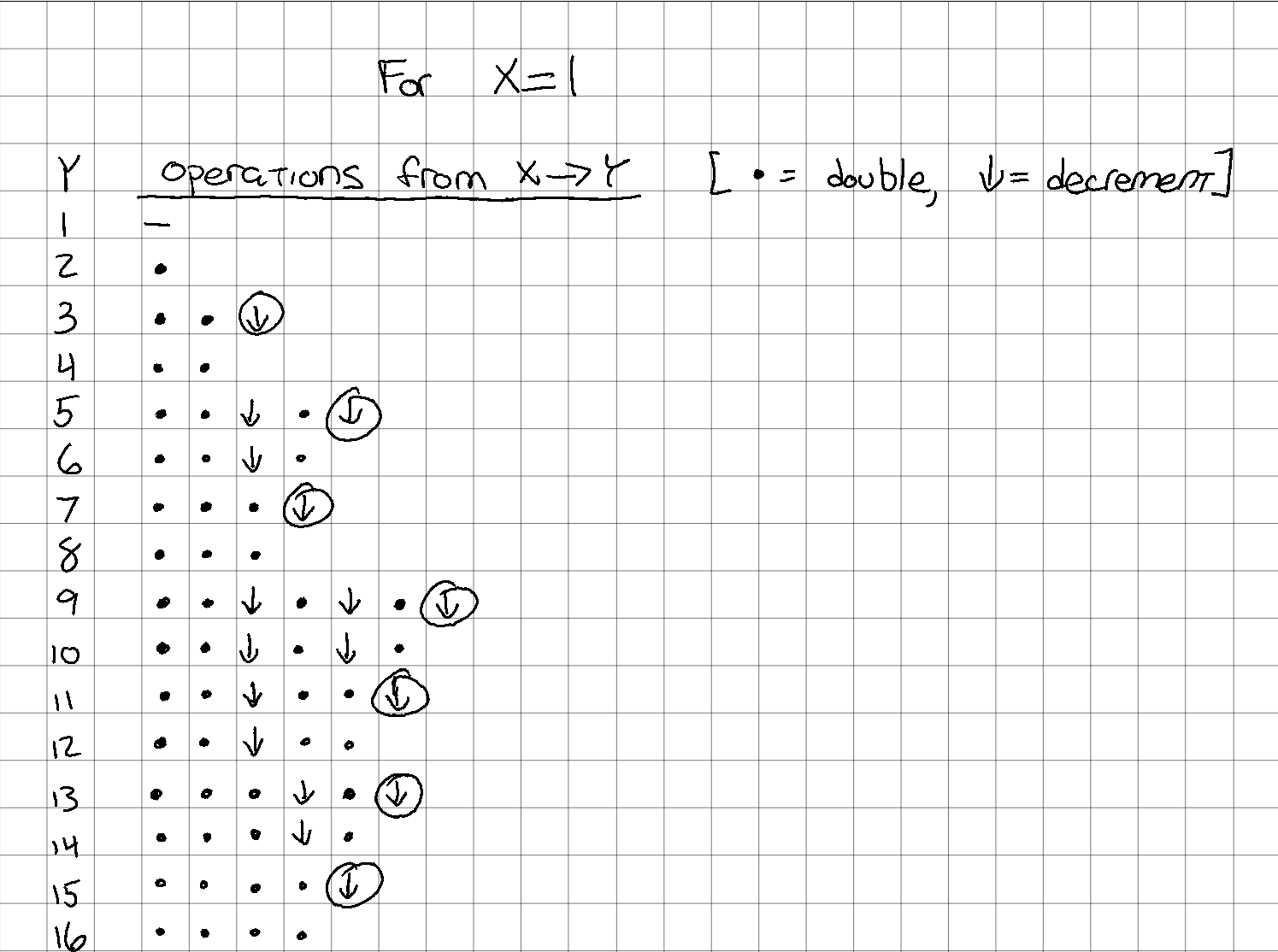

Even vs. odd

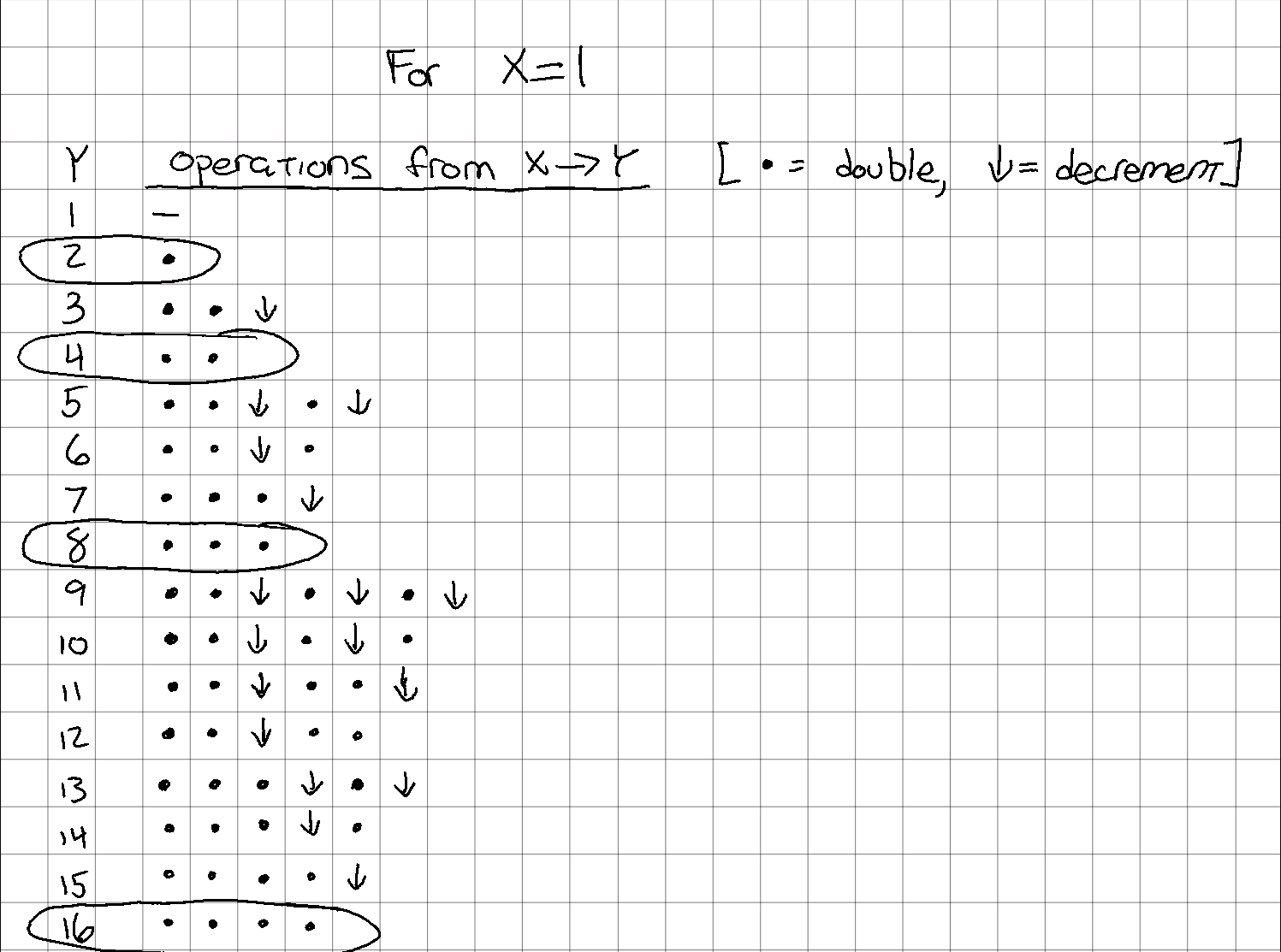

- There is a “powers of 2” element. Notice that (with $x = 1$, at least) the set $y = [2, 4, 8, 16, … 2^n]$ is composed solely of double operations, with no decrements.

$x \cdot 2^n$ has no decrements

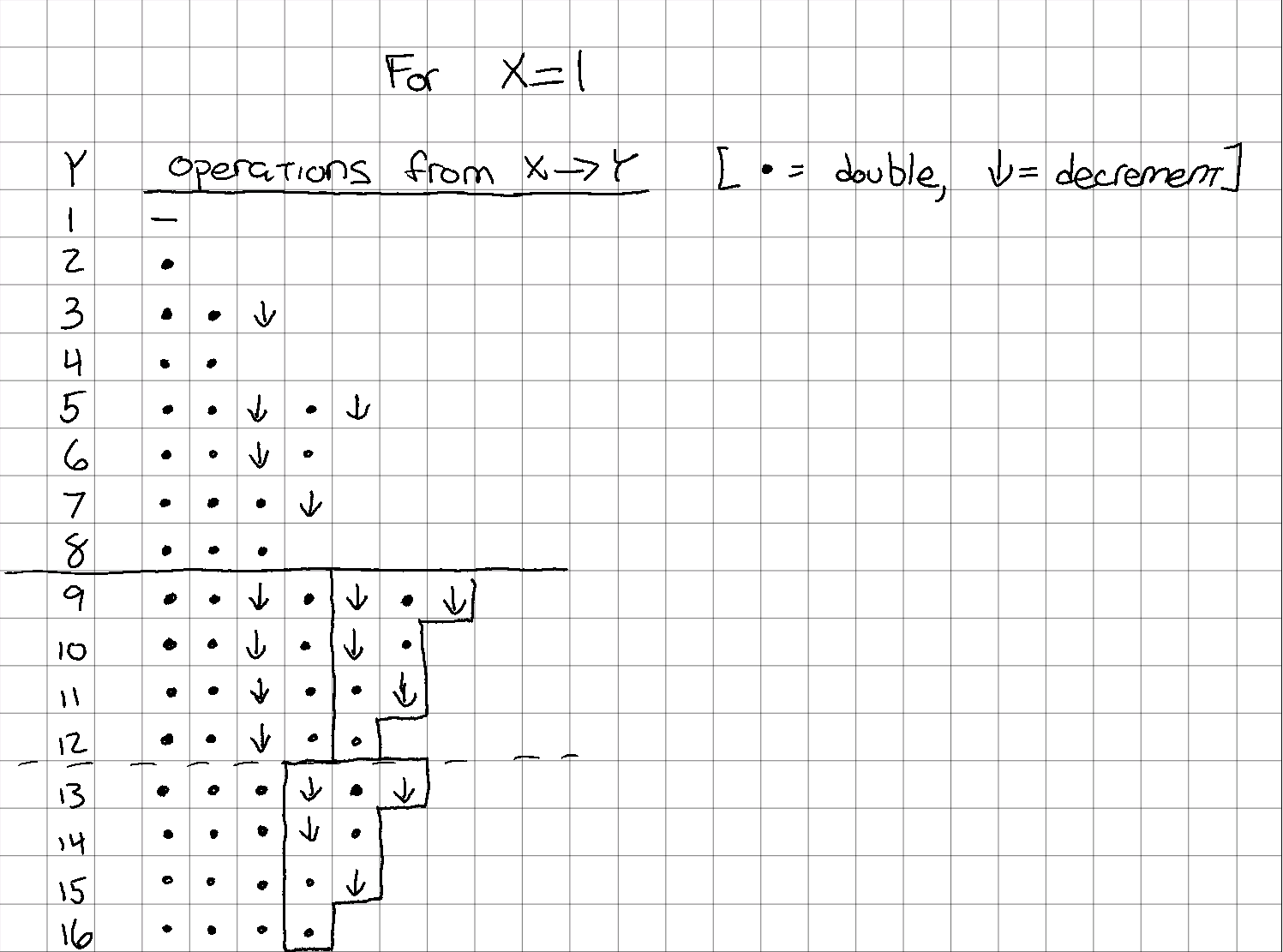

- In addition to the above, one can also see that there are the same number of double operations for all numbers in the set $y = [2^n + 1…2^{n+1}]$. For example, each of $y = [9, 10 … 15, 16]$ has exactly 4 double operations, with varying numbers of decrement operations. The same is true (but with exactly 3 double operations) for $y = [5, 6, 7, 8]$.

Same number of double operations in each ‘group’

- Comparing the $y = [9, 10 … 15, 16]$ set again, it appears that the “upper” half is a repeat of the “lower half”, but instead of each row having at least 3 double operations at the start, each has instead two doubles, a decrement, and then another double. Along with this, the “right side” of the pattern from $y = [13, 14, 15, 16]$ is repeated, but one operation “rightward”.

Repeating blocks

- Finally, the same pattern at the trailing edge of the $y = [9 … 16]$ set is also seen in the $y = [5 … 8]$ set, and looks like it might be starting in the $y = [3, 4]$ set, but isn’t complete.

Repeating blocks pt. 2

How does this make an algorithm?

So glad you asked…

Let’s start with same condition to handle the case when $y$ is less than $x$. There’s not much fun going on in that portion, since it’s just a matter of decrementing until you arrive at the result.

def min_ops_magic(x: int, y: int) -> int:

if y < x:

return x - y

Next, let’s take advantage of the fact that all values in $y = [2^n + 1…2^{n+1}]$ have the same number of double operations. This number of double operations is the same as the power of 2 for the upper bound of that group, or $n+1$ in the equation above.

In our example, the set $y = [9, 10, … 15, 16]$ contains all numbers such that $y > x \cdot 2^3$ and $y ≤ x \cdot 2^4$. So I’ll refer to these numbers as being in the “$n == 4$” group. If I use up those 4 operations, I’m left with this:

Use up $n == 4$ operations

So what I need to determine is:

- Given inputs $x$ and $y$, what is the smallest $n$ such that $y ≤ x \cdot 2^n$

There are a few different ways to code this. I’m also calculating the $2^n$ at the same time here, since we’ll need that later

Option 1

import math

from typing import Tuple

def next_pow2(x: int, y: int) -> Tuple[int, int]:

n = math.ceil(math.log2(y/x))

pow_of_two = 2 ** n

return n, pow_of_two

This option works because:

$$y = x \cdot 2^n$$

$$\frac{y}{x} = 2^n$$

$$log(\frac{y}{x}) = log(2^n)$$

$$log(\frac{y}{x}) = n \cdot log(2)$$

$$\frac{log(\frac{y}{x})}{log(2)} = n$$

$$log_2(\frac{y}{x}) = n$$

Rounding $n$ up to the next highest integer means we can solve for $n$ anywhere in the given range.

Option 2

from typing import Tuple

def next_pow2(x: int, y: int) -> Tuple[int, int]:

n = 0

pow_of_two = 1

while x * pow_of_two < y:

pow_of_two <<= 1

n += 1

return n, pow_of_two

This option uses bit-shifting to count how many times we need to shift a bit left (starting from binary $1$), which is the same operation as incrementing $n$:

$$0001 == 1$$

$$0010 == 2$$

$$0100 == 4$$

$$1000 == 8$$

Initially I thought that Option 2 would’ve been faster, but after some timing checks it seems I was wrong, and the log2() operation was noticeably quicker.

Option 3

from typing import Tuple

def next_pow2(x: int, y: int) -> Tuple[int, int]:

n = int((y - 1) / x).bit_length()

pow_of_two = 2 ** n

This option is similar to Option 2, but it uses a Python built-in method on the integer type to return how many bits are needed to represent the number. The upper limit (16, here) has one more bit than all the other numbers in the group, so I subtract that out first.

Option 3 was the one I discovered last, and is the quickest of the three. If you have a faster way to calculate this number in Python, I’d love to hear it!

Let’s add Option 3 to our algorithm. I’ll inline it since I don’t need to call from anywhere else:

def min_ops_magic(x: int, y: int) -> int:

if y < x:

return x - y

n = int((y - 1) / x).bit_length()

pow_of_two = 2 ** n

The “magic”, Part 1 - LSBs

OK, this is where I thought things started to get a little weird. I’m sure there’s a great mathematical explanation for it, but I can’t exactly see it yet. Let me show you how I got to the answer, though.

If you look back up at the previous diagram, you’ll see I grouped the remaining operations in a specific way. There is a J-tetromino (rotated 180°) that’s repeated in both the upper and lower halves of the group, and an I-tetromino that only occurs on the top half, and pushes the upper J out by one. And no, the fact that there’s Tetris pieces in this puzzle isn’t the weird part.

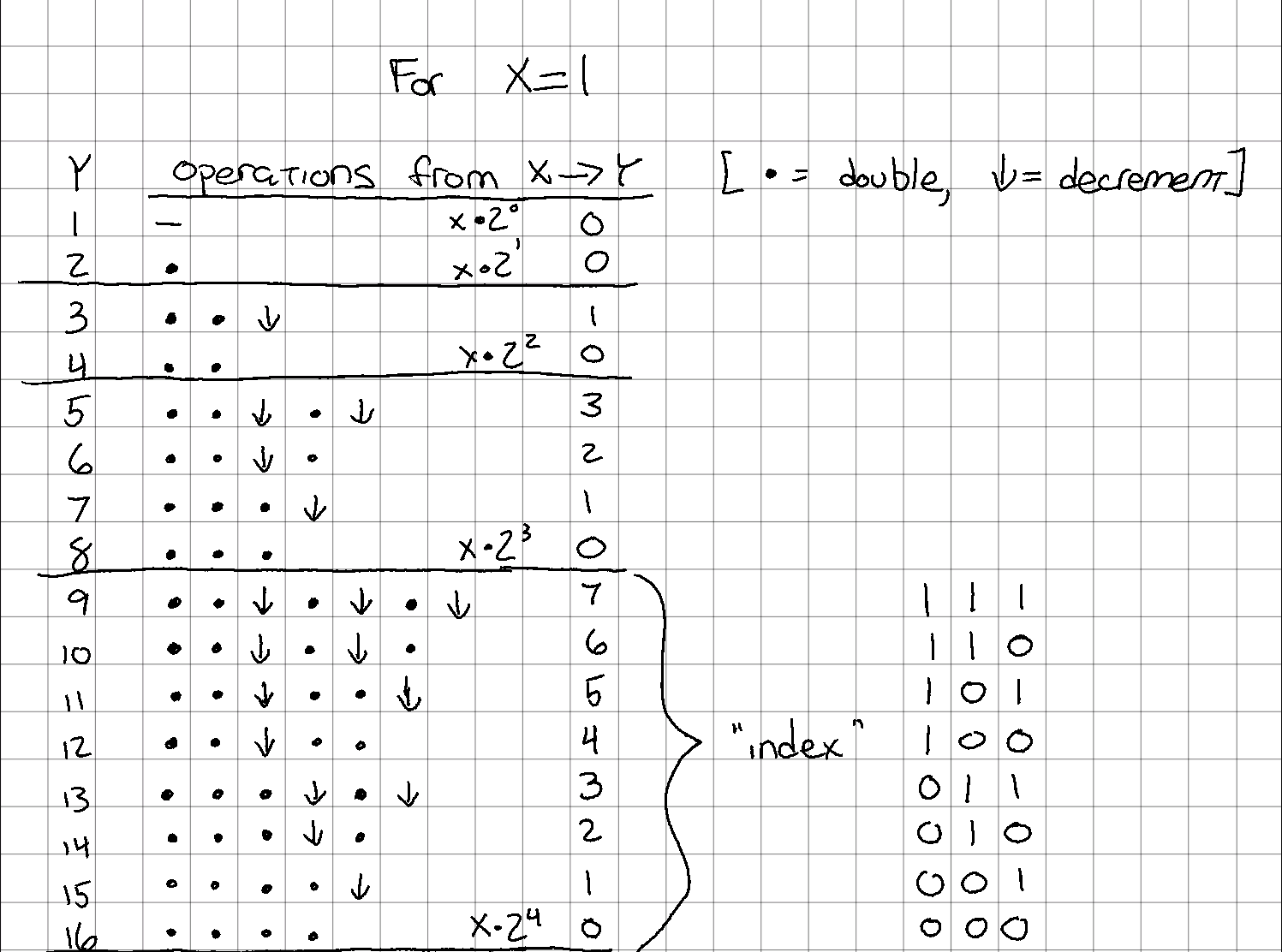

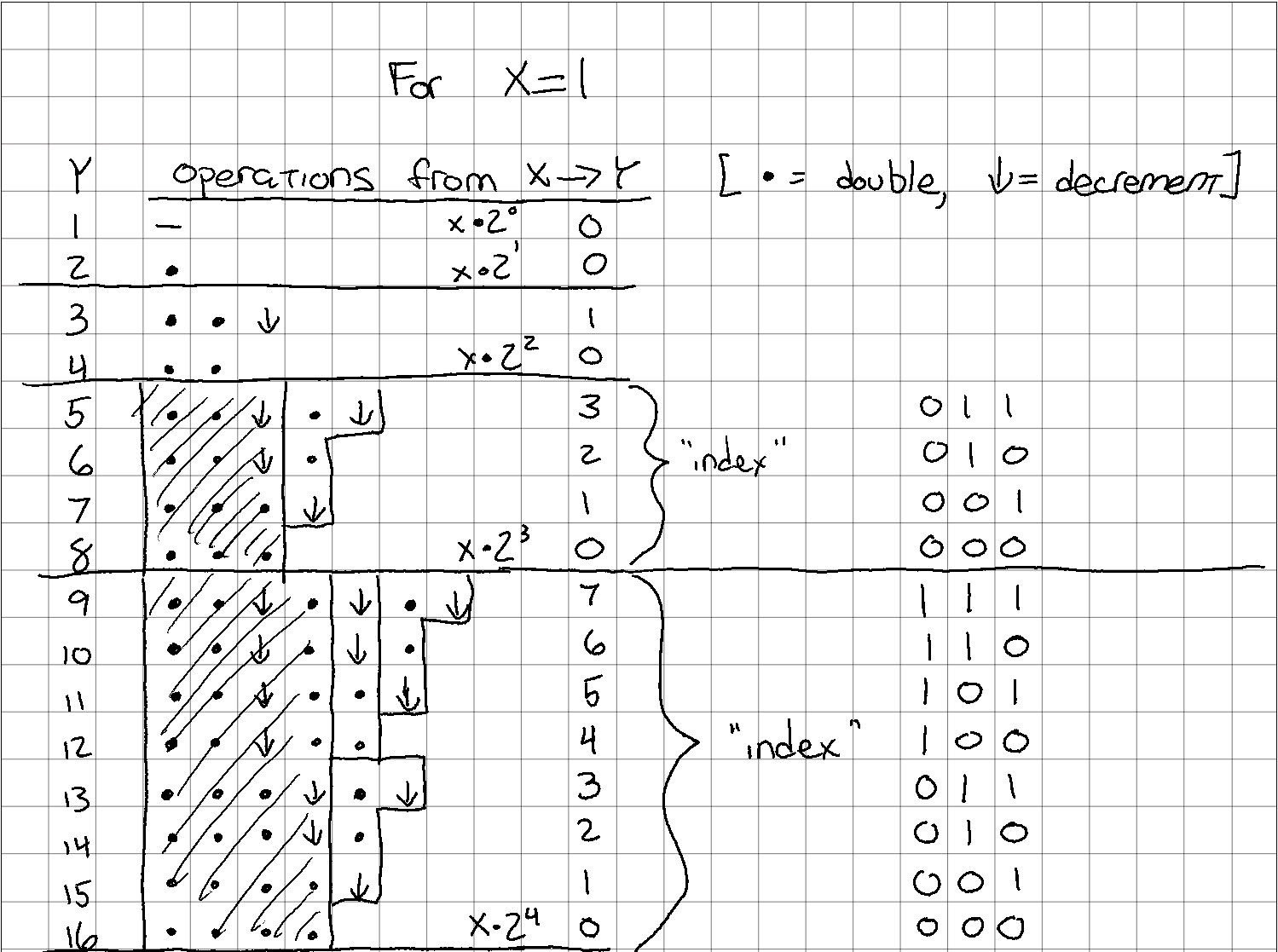

Based on the work from the previous section, I thought it made sense to number the rows counting upwards and starting at the upper bound. It’s probably not clear what I mean, so here’s another diagram.

idx of each row

After fiddling around for rather a long time trying to figure out how to calculate the number of operations expressed by each row, I happened to write out the index value out in binary:

idx of each row, in binary

See the pattern? I didn’t at first, either. Try now:

idx of each row, in binary, with hints

There’s a very tempting, obvious, and generally incorrect solution that involves adding all the “1” bits of the index number to get the remaining operations needed. In fact, it does work for the case I’m showing here, but it doesn’t work for all cases. I’ll get to that part in a second. Hopefully for now you can just take my word for it, at least for a couple more steps.

Instead of adding all of the “1” bits together, I only want to add $n$ least significant bits. I know, I know… in this case that means all of the bits. But I promise that’s not the case for all $x$s and $y$s.

Let’s get some more code going. This is only an additional two lines, so I’ll just add it to the algorithm we already have and highlight the changes below:

def min_ops_magic(x: int, y: int) -> int:

if y < x:

return x - y

n = int((y - 1) / x).bit_length()

pow_of_two = 2 ** n

# count down from top of 'bin'

idx = x * pow_of_two - y

# sum the '1's of the `n` least significant bits

lsb_ones = bin(idx)[-n:].count("1")

Getting the index is fairly straightforward: just subtract Y from the highest number in this ‘bin’.

Summing up the “1"s in the $n$ least significant bits is pretty Python-specific, and there’s several other ways to do it as well. In Python 3.10 (which should be released this year), there’s actually a new int.bit_count() method which will do exactly this, and much faster. At any rate, this line is just converting the integer idx to a binary string representation, slicing only the last $n$ characters of that string, and then counting how many of those characters are "1".

Again, note that even though in this particular case the number of bits in these numbers happens to be 3 or fewer (for $n == 3$), that isn’t always the case, so we can’t count all of the bits.

We’re very close now. As promised, here’s a case where we we need to add one final term to get our total operations:

The “magic”, Part 2 - MSBs

I chose a somewhat-but-not-quite random $x$ value, and set of $y$ values for this example. Feel free to verify this works for other values, though.

Spoiler alert: it does

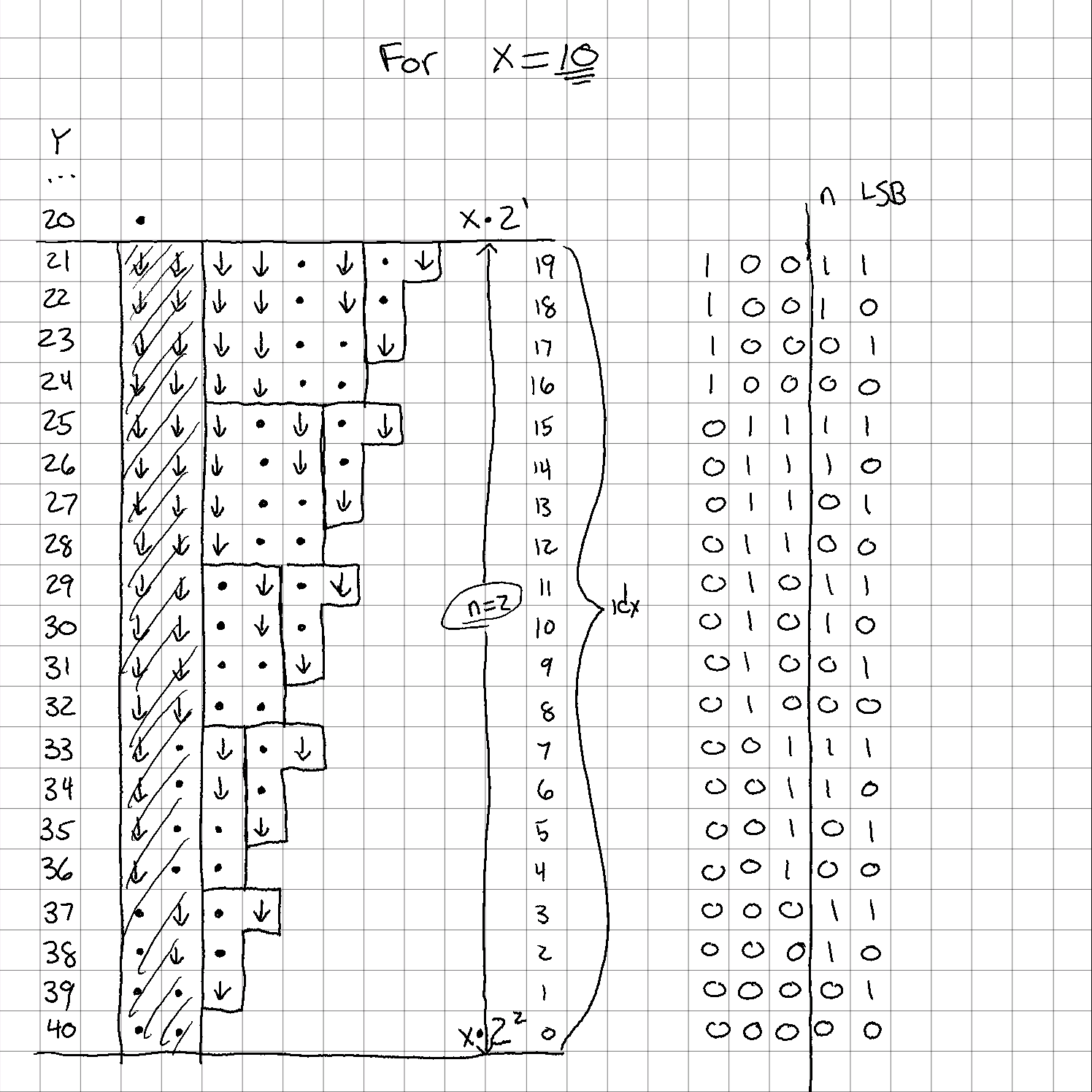

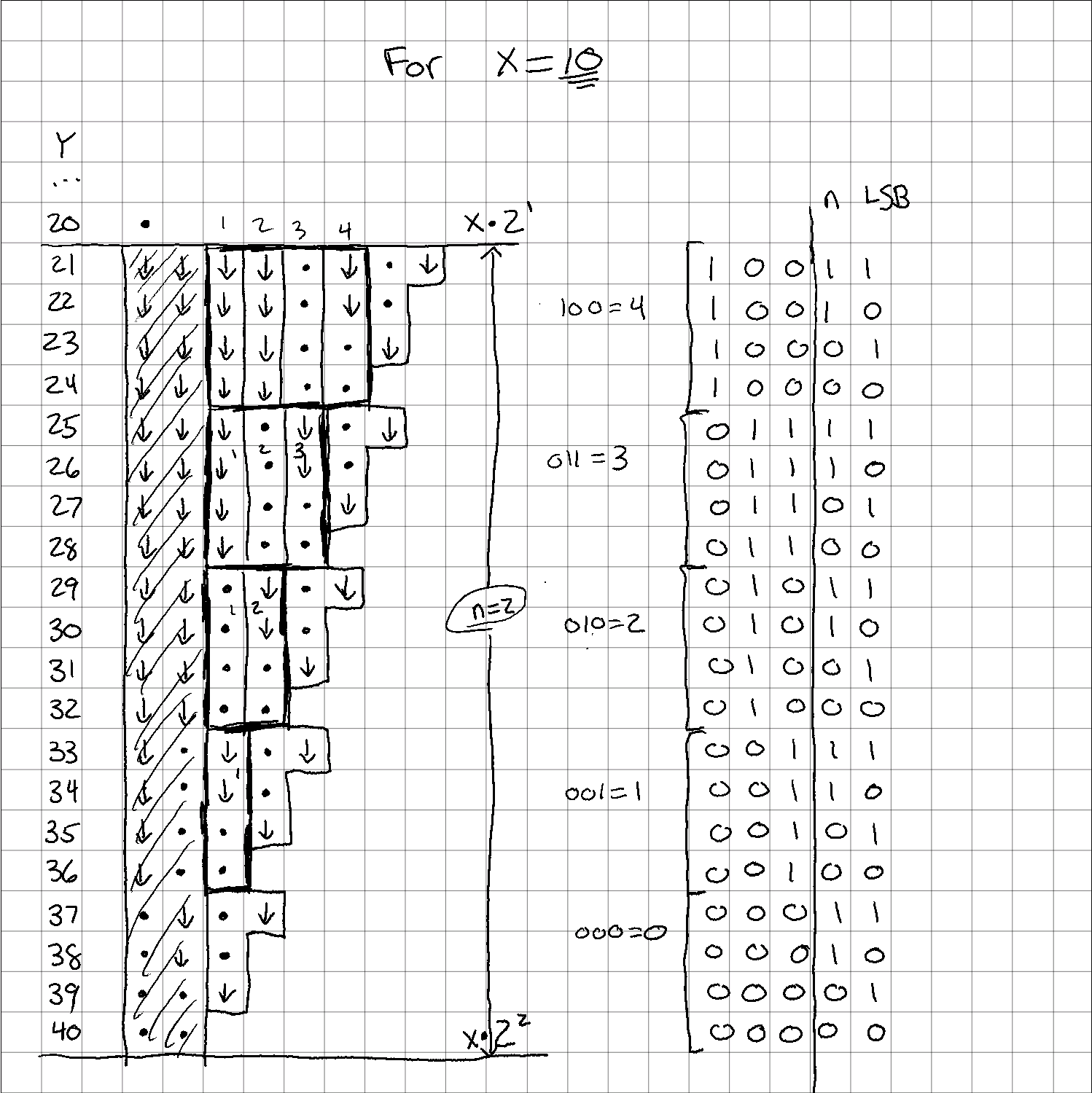

Let’s check with $x = 10$ and the bucket of $y = [21, 22 … 39, 40]$

Splitting MSB from LSB

Again, I’ve blocked out the $n=2$ operations, and am left with a few tetronimos, and some big boxes that would be a Tetris nightmare. You can see I’ve also filled in the idx values for each row and written them out in binary.

Remember how I said we can only use the $n$ least significant bits in the previous calculation? Take a look in this example what would happen if we used all of them. Wrong answers all over the place…

OK, so if we can only use the $n$ LSBs for that calculation, why did I write out all the MSBs anyway?

Only because this is the final piece of the puzzle.

For the LSBs, we just summed the number of “1” bits to get our J-tetronimos (tetronima? idk…) For the MSBs, though, we’re going to keep treating them as real numbers, but only after we’ve gotten rid of those already-used LSBs.

You’re probably way ahead of me on this, but you can see that if you treat the bits to the left of the vertical line as their own numbers, you get the number of extra columns needed to complete the total operations. Here it is a little clearer:

Treating MSBs as standalone numbers

All that’s left is a bit of coding:

def min_ops_magic(x: int, y: int) -> int:

if y < x:

return x - y

n = int((y - 1) / x).bit_length()

pow_of_two = 2 ** n

# count down from top of 'bin'

idx = x * pow_of_two - y

# sum the '1's of the `n` least significant bits

lsb_ones = bin(idx)[-n:].count("1")

# bit-shift `n` to the right to get only the MSBs

msb_vals = idx >> n

# the grand finale

return n + lsb_ones + msb_vals

Since we’ve already gotten what we needed from the $n$ LSBs of the index, just shift it right by $n$ bits to get at the MSBs that we care about. No special conversion needed after that - we’re still just treating it as an integer.

Finally, the answer to the question of life, the universe, and everything (or at least this LeetCode puzzle) is simply the sum of the 2’s exponent, the sum of the $n$ LSB “1” values, and the number represented by the leftover MSBs.

Crazy, right?

But was it worth it?

tldr; yes

Besides everything I learned from this (including a lot of brushing up on bitshifting math that I ultimately didn’t need for the solution anyway), I also ended up with a more satisfying (to me), faster (for most cases) solution. Your results may vary, but on my machine for an arbitrary set of ~80 different input conditions, the “magic” solution is ~20% faster.

Bonus points if you can see how this explanation relates to Hamming weight and/or to this unrelated coding challenge (sorry, I can’t find a link in English, but Google Translate works well enough).

As always, please do let me know if you find any mistakes in the code or explanation, or if you have questions. My contact info is on the main page.